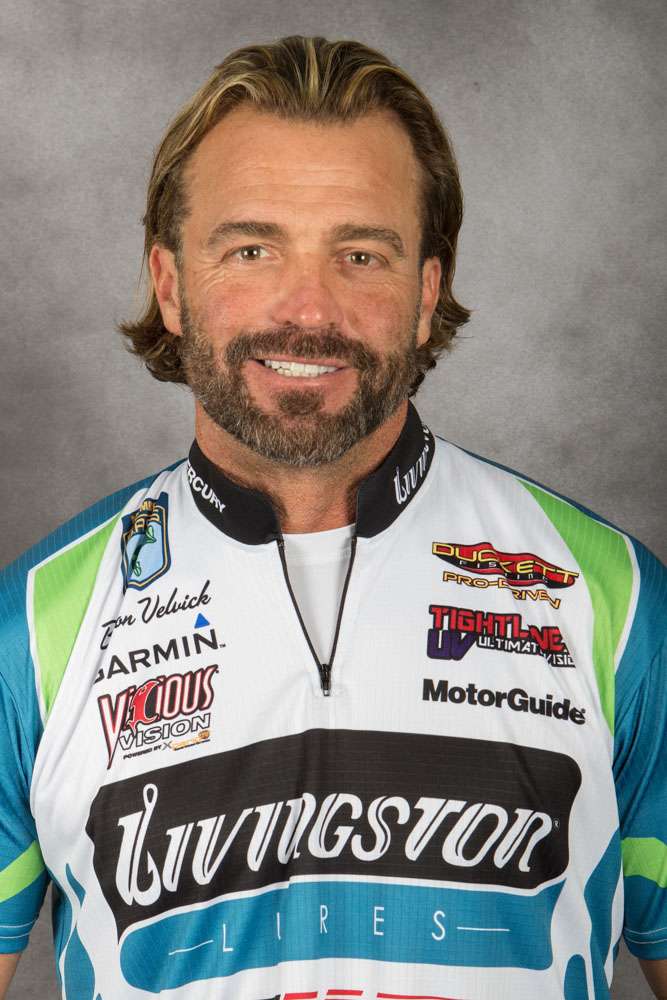

Editor's Note: Swimbaits are hot. Recognizing that, Bassmaster.com asked Elite Series angler Byron Velvick to write a series of monthly articles on "The Art of the Swimbait." He was one of the early pioneers in their development and currently is on the pro staff of Fish Harder Companies as a swimbait specialist. Velvick's thoughts, ideas and tips will help you catch more bass on these baits.

In this, the introduction to our series, it's appropriate to begin by trying to define what a swimbait is, and what it isn't.

When I think of a swimbait I think about an artificial lure that mimics a baitfish. It's a lure that's characterized by a lifelike action and a lifelike appearance, a lure that puts bass in the boat because they believe it's the real thing. They want to eat it.

It's not a reaction bait they want to kill, nor is it a flash bait they bite because they're curious. And size and weight have nothing to do with anything. There are swimbaits as small as 3 inches and as big as 16 inches. Some weigh much less than an ounce while others exceed 3 or 4 ounces.

It's not characterized by its construction, either. Some are made from soft plastic, others from wood or hard plastic. Some are jointed, but just as many get their action from a lip or from the engineering design of the bait's body and tail.

In short, a swimbait swims and looks like the real thing.

I started fishing with swimbaits in the ocean off the California coast in the early 1990s. I noticed that I caught rather small saltwater fish on really big baits. At the same time I was getting serious about bass fishing in freshwater. The lakes I was fishing were stocked with trout. In fact, they were the primary forage.

Around the same time a small group of California anglers were fishing for the world record with live bait — mostly crawfish. I reasoned that if they could catch giant largemouth bass on a tiny crawfish surely I could catch them on a big swimbait, especially if they were feeding naturally on big rainbow trout.

By 2000 I was hard into swimbaits. They were my bass fishing thing. I was attracted to them mostly because they were different. No one else was using them. My success was a closely guarded secret. So secret that when I caught one on a big bait during a tournament, I'd express surprise that it actually caught something. That kept my co-anglers from catching on and spreading the word.

All of my baits were handmade at the time, and most of them resembled rainbow trout in one form or another. Commercial production was non-existent. You either made them yourself in the garage, or you didn't have any. Over time, though, a few small custom shops began producing them. But even then they were mostly one of a kind special order items.

Over time my swimbait skills matured. I quickly learned the single most important lesson about these baits: Without exception, a swimbait must match the hatch. If it doesn't, it's useless.

Matching the hatch isn't just about color, or size or movement. It's about all those things combined. A good bait must look like the real thing. First, that means the color must match the color of the prevailing forage. The best tilapia bait in the world won't be successful in a lake that doesn't have tilapia in it.

Bait color is also affected by water color. Colors don't look the same in clear, slightly stained and muddy water. They take on a different appearance. The lure must look like what's in the lake given the current water conditions.

Size is another factor. A 4-inch thin bait looks very different than a 4-inch fat bait. They make different profiles when pulled through the water. Size isn't just about length. It's about bulk and the appearance of bulk, too.

Think of it this way: A rainbow trout doesn't have the body shape of a bluegill. So a rainbow trout finish on a bluegill body doesn't match the hatch, regardless of how accurate the colors may be on it. It doesn't look right. It doesn't have the right bulk.

Finally, we come to movement. Motion is made up of two parts — lure design and angler retrieve. A good swimbait — one that catches bass — must be engineered to swim like the real thing. If the lure isn't capable of a natural swimming action, you can't catch fish with it.

Next, your retrieve must match the real thing. If the local baitfish swim long distances without stopping or changing speed, your retrieve should duplicate that. If, however, the local forage stops and starts as it swims along, your bait should do the same.

That's the beginning. Next month we'll cover how to choose swimbaits — keeping in mind that you can't afford to buy one of everything — for the venues you're going to be fishing. We'll also take a look at rods, reels and line.