As increasing warmth bolsters spring’s enlivening influence, big fish are putting themselves in vulnerable positions for those who know where to look. Five Bassmaster Elite Series anglers shared their insights into how they track down and engage April giants.

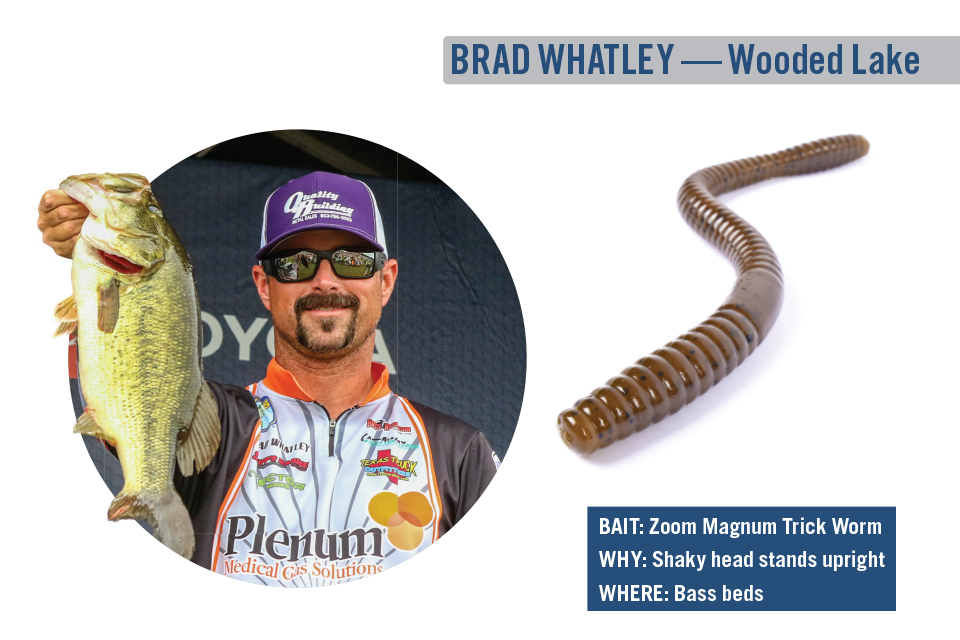

Brad Whatley

Framing his April focus in no uncertain terms, Brad Whatley said, “It’s all about the flats. I completely avoid creeks; I don’t give two flips about the creeks this time of year.”

On those flats, he finds stumps his most consistent giant-fish magnet (assuming it’s a lake with minimal vegetation). Whatley will fish every one he can find, but spotting a stump with a prominent root system or a depression between two stumps on his Humminbird MEGA 360 makes him especially optimistic, as these are the makings of big-bass bedding sites.

In his view, truly capitalizing on such opportunities requires something outside the norm — something that will tempt, taunt and tick off a big bedding bass.

“Because this is a spawning situation, I’m not looking for a fish that’s going to chase anything down,” Whatley said. “Everybody flips Texas-rigged baits, but several years ago, I learned a technique that has allowed me to win [a lot of money] in local events — a Magnum shaky head on 20-pound fluorocarbon.

“That time of year, I’ll be in less than 10 feet, so it’s going to be a 1/4- to 3/8-ounce [head] with a Zoom Magnum Trick Worm. All you’re doing is dragging it by that stump and shaking it.”

Whatley said he’ll cast a few yards past the targeted stump, let the bait settle and drag it to the stump. Once inside the stump’s perimeter, he’ll slow down and move the bait a couple of inches, shake it and repeat multiple times to traverse the red zone.

“It’s basically blind fishing for bedding fish,” Whatley said. “Unlike a Texas rig that just lies on the bottom, the shaky head stands up in their face and they can’t handle it.

“I may make that cast last a minute, especially if I believe in that piece of cover or if I have any history with that area.”

Before reeling in, Whatley gives his bait a quick 2- to 3-inch snap to make it hop aggressively. Taking a page from his sight fishing playbook, he knows that a stubborn fish that intently watches an intruder and occasionally tail drags it out of the bed will trigger on the sharp movement.

“They’re looking at that bait when it suddenly moves 900 miles an hour over their nose; they inhale before they even know what they’ve done,” Whatley said. “I’m just envisioning there’s one on the bed right before I reel it in, and I get a lot of big bites doing that.”

Greg Hackney

Most of the year, tides definitely trigger feeding and make good things happen, but during this season, Greg Hackney knows the giant bass he seeks typically try to avoid fluctuating water. Real simple here: Too much movement threatens bed security, but even those on their way out are in no hurry to leave.

“That time of year, I’ll be looking for some kind of dead end — something that doesn’t have current,” Hackney said. “Typically for us [in southern Louisiana], those fish are postspawn in April, but they typically linger around the places where they spawn because it hasn’t gotten hot enough yet to move them back out to main-current breaks where they’ll summer.”

Hackney most often finds his desired scenario in the man-made canals cut through the delta marsh. Usually accessing drilling industry equipment and facilities, these muddy arteries provide bass spawning habitat similar to a lake’s natural creek or cove.

“It can be any type of structure in that canal, maybe a point, maybe the intersection of two canals; it could even be where a canal intersects with a natural bayou or a place where the water’s draining out of the marsh into a canal,” Hackney said. “They’ll be setting up to feed that time of the year, so they’ll be setting up on really obvious places.

“They’ll be more toward the back ends of those places when they spawn, and it seems like they pull out to the fronts of those places during the postspawn period.”

A strategy applicable throughout the South, as far away as the St. Johns River, matted vegetation plays a big role in April — but not as big as it will in the coming months. This time of year, Hackney finds his fish more around the edges than actually under the cover.

“We don’t always have a shad spawn, but when we do, they like to spawn around those hyacinth mats,” Hackney said. “Those fish are looking for an easy meal, just like they would anywhere in the country. They’re looking for an easy place to set up and [regain their weight] after the spawn.”

Hackney has found the best way to entice these fish is with a weedless topwater presentation. His picks: The Strike King KVD Sexy Frog and the Popping Perch.

“Typically, it’s slow fishing; I’m walking it around the edge of that grass,” Hackney said. “Those fish are looking for something easy and something big. When I want to disturb more water — if it’s windy or raining, maybe the water is dirtier — I’ll throw the Popping Perch.

“Sometimes, in those canals, the water will be gin clear, and when it is, I typically throw the Sexy Frog. The body size is almost identical, but it’s more subtle. I’m more on that Popping Perch when I’m trying to draw them out of superthick stuff or if I want to create more commotion.”

Jonathan Kelley

While April could find fish on beds, Jonathan Kelley expects to encounter his best shot at a river giant in a prespawn position. That means leveraging key spots just off the main current.

“Those big fish get big for a reason; they relate to that main current heavily,” Kelley said. “Some of the [best] areas where you’re going to find them are a channel swing or a deep outside edge off the channel where a lot of current pushes through. Any little eddy or break is a potential area where some of the biggest fish are going to stay that time of year.”

Scenarios will vary, especially with different river depths, but the consistent criteria comes from finding the key structures situated on the contours over which the current washes food. A good example: A deeper channel swing pushing into the point of a rockpile.

“It’s a similar concept on a shallow river,” Kelley notes. “You have to imagine where that channel is going to push the heaviest and hardest. Somewhere around that area, there’s going to be current breaks, and I believe that’s where the biggest fish typically like to set up the most.”

While he finds a drop shot or a jig sufficient for deeper spots, Kelley tackles the shallow-river scenarios with a two-pronged strategy. The first job is locating a productive area, then he’ll pick it apart.

“A lot of those fish generally do like to react, so your crankbait, spinnerbait and ChatterBait are definitely key,” he said. “You’re going to be able to catch fish flipping or pitching a bait, as well, but to find those productive areas, you’re going to want to rely on those moving baits because you can cover more water and potentially come across more areas.

“If I feel like I can get bit on a moving bait, generally, I think you can slow down and catch multiple fish on a 1/2-ounce flipping jig with an X Zone Adrenaline Craw Jr. trailer.”

Kelley points out that he has experimented with different jig sizes but finds the 1/2-ounce affords him the optimal blend of presentation accuracy and efficiency. Specifically, a river’s countless unseen obstructions present unacceptable challenges for lighter jigs.

Clent Davis

Typically, the new grass has yet to top out by this time, so Clent Davis leverages the opportunity to tempt big fish with a big meal that requires only a little bit of effort. His preference: a Yo-Zuri 3DB Pencil 125 in bone color. Superclear conditions may require a translucent color, but the principle remains the same.

“That time of year, the water’s so warm, I’ve probably caught more big ones on topwater than anything,” Davis said. “Big fish usually like to live somewhere close to deep water. You’ll [occasionally] catch them out of a foot, but there’s usually some kind of a breakline close by, so they have quick access to it.”

Also, Davis often finds his best opportunities exist around isolated clumps of grass amid the larger field. The biggest fish tend to value their privacy, so he’ll pay particular attention to some of the most unassuming sections, as long as they’re near the depth break.

With hydrilla and milfoil still shy of breaking the surface, Davis stays as far back as possible and makes long casts without risk of spooking bass. On his Coosa River home waters, he’s mostly targeting isolated water willow, in which case, he’ll parallel the emergent cover. In any habitat, Davis knows that speed kills.

“Usually, a big fish likes something moving slowly,” he said. “I use a really slow cadence, maybe stopping here and there.

“Ideal conditions would be some kind of front; not necessarily a cold front — even raining. I catch more on topwaters when it’s raining than any time, but I definitely like it cloudy.”

Davis mostly targets creek mouths and focuses on main-lake points and pockets. While this pattern could cross paths with a late prespawner, Davis knows he’s most likely fishing for those on their way out the door.

Fish that are moving up, he said, tend to focus lower in the water column. Conversely, those postspawners are ready to eat, and a walking topwater fits the vulnerability profile.

“I’m not covering a lot of water; I’m just picking apart those isolated spots,” Davis said. “Little bitty inside turns off of a point where a fish will set up and spawn are great. Everybody thinks all your bass run to the very back of a pocket, but some of your biggest bass are just barely off the main lake.”

Fishing his topwaters on 50-pound Yo-Zuri SuperBraid, Davis offers this tip: “If you’re worried about the front hook catching on your braid, I run a couple of bobber stops right in front of the line tie. That keeps the line from bunching up in front of your hook.”

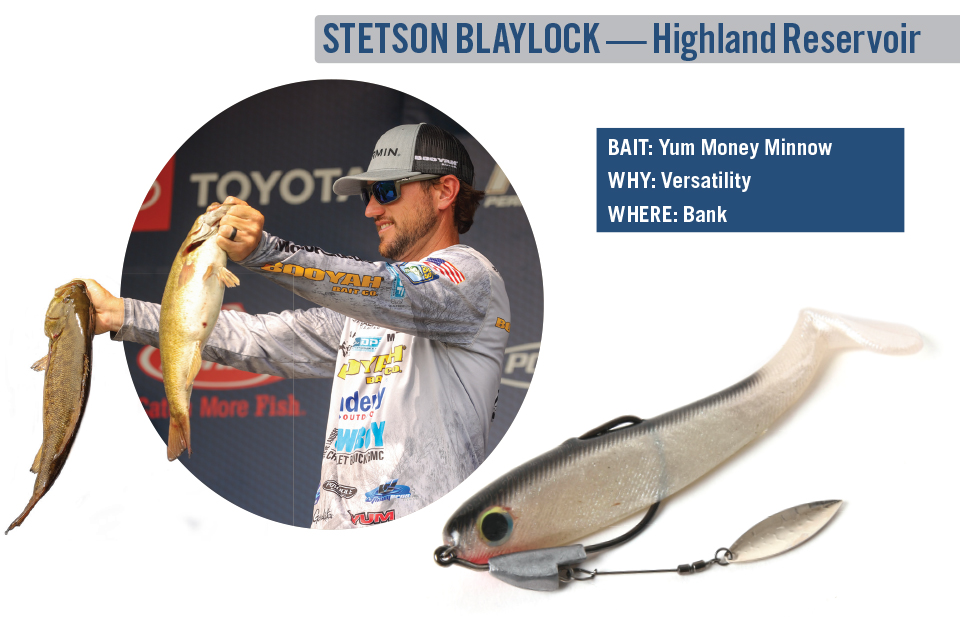

Stetson Blaylock

Because the fourth month could offer all three stages of the spawn, Stetson Blaylock disciplines himself to first determine what a given lake is offering. Time maximization, he said, demands a plan that covers the coming/going stages, as well as the shallow game.

“April is my favorite month of the year, and if you’re talking about one giant bite, I’m going to be going down the bank, looking at them; I’m going to be visually trying to find that fish,” Blaylock said. “I’m going to be casting a Texas-rigged Yum Christie Craw [white and watermelon options] and a wacky-rigged Yum Dinger to see what the fish react to the best.

“I’m also going to have a big swimbait tied on, because in the springtime, you have to keep them honest; you have to have a search bait. I’m throwing that swimbait over points where I’m trying to get pre- or postspawn fish to react to it.”

Blaylock employs two swimbait styles: a 5-inch shad colored Yum Money Minnow on a Gamakatsu Spring Lock Spinner hook (willowleaf blade suspended from the weighted shank) and a 5- or 6-inch Scottsboro line-through model. This pairing allows him a one-two punch that covers his swimbait objectives.

“That Money Minnow is going to be my go-to in a highland reservoir because I can fish it like a spinnerbait or an umbrella rig — it’s kind of a three-in-one style approach,” Blaylock said. “With the Scottsboro swimbait, make the longest cast you can make and reel it as slowly as you can — it’s the opposite of the Money Minnow.

“You can actually pitch the Money Minnow up on the bank [to search for bed fish], but I would just prefer the slower stuff like the Dinger and the Christie Craw.

“If it’s my first trip to the lake, I’m going to troll down the bank first and just look,” Blaylock said. “If I’ve established that there are more fish in pre- or postspawn, then I’m going to start in low-light conditions with a swimbait and then make my way to the bank.

“But if I’ve established that there are more fish on the bank, either in the spawning mode or up there getting prepared to spawn, then I’m going to go straight to the bank.”

Originally appeared in Bassmaster Magazine 2022.