If you’ve fished the Ohio River near Lawrenceburg, Ind., then you know about Tanners Creek. It has plenty of shoreline flipping targets, but Tanners is also a deeper-water creek, so it’s one of the most popular tributaries on that part of the Ohio. Most tournaments launch there, which is why Bill Lowen was in Tanners one fateful day 20 years ago.

The trouble is, he’d been going down the bank flipping a jig all morning but hadn’t had a strike. Then, when he came to a particularly big laydown, he flipped his jig in as he’d been doing and let it sink to the bottom. Once again, nothing happened — until Lowen reeled the lure up to make another flip. A solid 3-pounder raced up out of the branches but missed the jig.

“That was encouraging,” remembers Lowen, now an established Bassmaster Elite Series pro preparing to compete in his seventh Bassmaster Classic, “but the light didn’t really turn on for me for another hour. I kept flipping down the bank until I came to another big laydown, and once again, as I was reeling my jig up through the limbs, a 2-pounder came up, but it also missed the jig.

“Those were the only two fish I’d even seen all morning, so I decided to cast and simply reel my jig back, and when I did, a 3-pounder just ate it. That afternoon, just casting and reeling my jig, I had 20 bites, which is phenomenal on the Ohio River. That’s how I discovered the technique of swimming a jig, and I’ve been doing it ever since. It’s a major part of my fishing now, and I don’t roll out of the dock at many events where I don’t have a swimming jig tied on.”

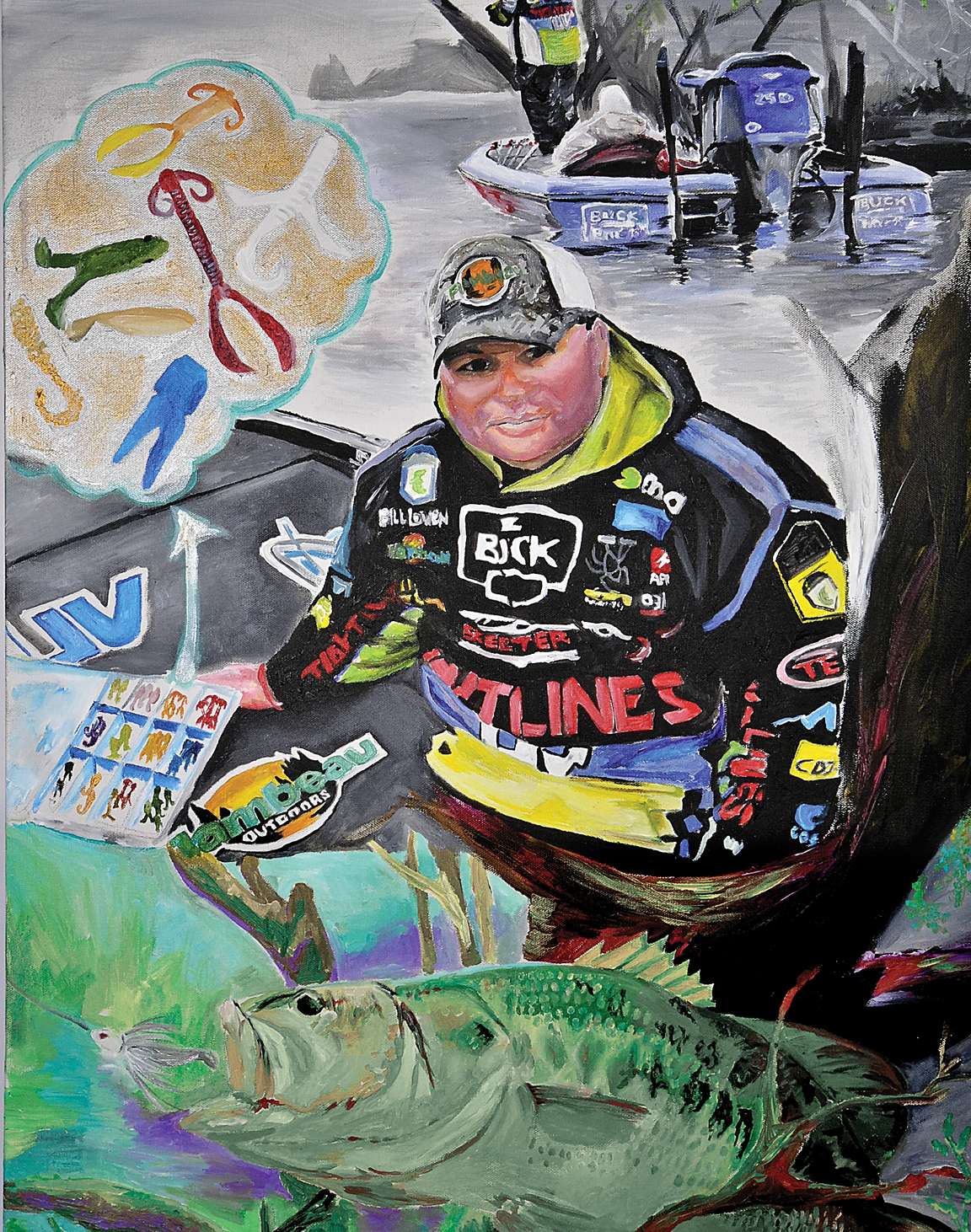

Swimming a jig is more than a major part of Lowen’s bass fishing strategy; it’s his trademark, and few, if any, do it better. Certainly, no other bass pro uses the presentation more than he does. He’s designed jigs specifically for swimming for Davis Bait Co. out of Sylacauga, Ala., as well as a special swimming jig rod for Castaway Rods out of Montgomery, Texas, and he’s given countless seminars around the country teaching others how to do it.

“I call swimming a jig a finesse-power presentation,” Lowen explains, “because it’s very subtle and very natural, but I do it with a heavy action flipping rod and 30-pound braided line. The actual presentation could hardly be easier, too. Day in and day out, I basically just cast my jig and reel it back, but really, any retrieve you use with a spinnerbait you can also do with a swimming jig.

“You can reel it up to cover and drop it. You can shake your rod as you’re reeling. You can do anything you want, but always remember, swimming a jig catches a lot of bass, and they’re going to be quality fish, because the jig looks so natural in the water.

“That’s why I just cast and retrieve, swimming the jig slowly but steadily back. If you look at a shad, a bluegill or even a crawfish when they’re swimming, they’re always swimming straight. When you’re swimming a jig, you’re not trying to imitate something injured or acting erratically, you’re emphasizing how subtle and natural the lure looks. Just sliding through the water, it doesn’t have a lot of vibration or flash, but it does appear [to be] an easy meal, which I think is why bass can’t resist it.”

The real beauty of this technique, emphasizes Lowen, is that it is primarily a shallow-water presentation. He rarely swims a jig deeper than 8 feet, and 4 to 6 feet is his favorite depth. Specific cover, such as those laydowns in Tanners Creek, is not critical, either, as Lowen has caught bass swimming his jig across gravel points, over sandbars and in river current.

“Anywhere you throw a spinnerbait is a place I throw a swimming jig,” continues the Elite Series pro, “and the way I start on most lakes or rivers where we compete is in shallow water, and generally around some type of cover. I’ll just ease down a shoreline, casting to boat docks, flooded bushes, grasslines and anything else I come to. I keep the jig up where I can see it all the time as I retrieve, so I’m staying in relatively clear water. Probably the only time a swimming jig is not productive is in extremely dirty water.”

If working down a shoreline doesn’t produce any action, Lowen starts going a little deeper, moving out but still casting toward shallow water, and retrieving the jig 5 or 6 feet down — again, with slow, steady reeling. If he doesn’t get any bites by working the water column at that depth, he’ll probably put the jig away and try something different. Lowen limits himself to shallow water like this with a swimming jig because below about 8 feet he thinks other lures and presentations become more effective.

Exactly where Lowen swims a jig depends on the lake he’s fishing. On grass lakes such as Toledo Bend and Sam Rayburn, he retrieves over the top of sunken hydrilla. On Kissimmee, he likes lily pads. Sometimes on the Tennessee River, he stays in the current, letting the water’s movement help push the jig downstream.

“If I had to name a perfect scenario for swimming a jig, it would be for prespawn bass staging in shallow water around flooded bushes and other vegetation,” he says, smiling. “But I throw a swimming jig all year. One of the things many fishermen don’t realize is that you can use a swimming jig just like a regular jig, such as swimming it up to a target, then letting it fall to the bottom, then swimming it back up to the surface. Conversely, you can swim any style of jig you own, but some are designed specifically for swimming and are definitely better than others.”

What probably surprises most who study one of Lowen’s swimming jigs is that it features a bullet-type head, rather than a flatter design that would seemingly swim better. Lowen’s bullet-head design, however, comes through grass and vegetation much more smoothly. Part of the reason is because the bullet head also has a rounded belly — he compares it to a bass boat hull — which not only helps when the jig is coming through cover, but also helps the jig to lift, not dive.

That’s why all Lowen has to do on his retrieves is reel the jig back to him. He does not have to force it to come up with a lot of extra rod action. His everyday favorite weight is 1/4 ounce, but when he moves to deeper water, he changes to 3/8 ounce, and on occasion he’ll even go as heavy as 1/2 ounce, but not often. In cold water, he drops down to an 1/8-ounce jig, a lure he often fishes in very early spring when he can just float it over vegetation with very little action.

Through his years of experience, Lowen has also learned his rod and reel choices play a critical role in the swimming jig presentation. His reel is a fast Abu Garcia Revo with 7.1:1 gearing — a choice, Lowen says, dictated by the bass themselves. Some bites are so fast and so violent that he can’t keep up with the fish unless he has that fast gearing. He fills the reel with 30-pound Trilene braided line (with the 1/8-ounce jig, he uses 8-pound fluorocarbon), which is still limp enough to cast the 1/4-ounce jig but strong enough to pull those fish out of the hydrilla and brush. Using heavier braid, he says, is like fishing with rope.

“Overall, I think the biggest key for me in swimming a jig is not the reel or the line or even my jig, but rather, my rod,” continues Lowen, who describes his own rod choice as a flipping stick with a spinnerbait tip. “I use a 7-foot, 6-inch rod with a lot of backbone, but it has a very light, fast tip. The fast tip actually vibrates as I retrieve, so it gives the jig a little action as I swim it through the water. At the same time, the soft tip flexes when a bass takes the jig and gives me that extra fraction of a second to set the hook. I think my hookup ratio is close to 99 percent with my rods, just because of that tip and the lack of stretch in the braided line.”

The final part of Lowen’s swimming jig arsenal is the trailer he puts on his jigs, and he has three different categories he uses, depending on what the bass tell him to use. Still, he emphasizes there is no magic trailer for all seasons and the best place to start is with any piece of plastic that gives you confidence.

The final part of Lowen’s swimming jig arsenal is the trailer he puts on his jigs, and he has three different categories he uses, depending on what the bass tell him to use. Still, he emphasizes there is no magic trailer for all seasons and the best place to start is with any piece of plastic that gives you confidence.

“Most of the time, a trailer that has a curly or swimming tail, such as a single- or double-tail grub, will work on a swimming jig,” Lowen says, “and this is often where I start. If I don’t want any action at all, I’ll use a chunk-type trailer or a beaver, but if I want a lot of action and vibration, I’ll put on something that has a lot of legs and flappers so it moves a lot of water.

“The one exception I make to this is when I know the bass are feeding heavily on shad and nothing else, such as in the autumn. Then I use a small swimbait style of trailer that has a paddle tail.

“My basic rule of thumb for swimming a jig is the colder the water, the slower I swim the jig and the less trailer action I want. I have caught bass swimming an 1/8-ounce jig with a small plastic chunk trailer in 40-degree water.

“On the other hand, the warmer the water, the more action bass usually want. I retrieve faster and use either a double-tail grub or a creature-type bait as a trailer.”

Color-wise, Lowen tries to match his jig and trailer with the dominant forage bass are feeding on, and he usually coordinates his jig and trailer colors. His primary choices are black/blue, white and green pumpkin. The exception often comes when he’s swimming jigs for smallmouth, when he uses pink-and-white jigs with pink trailers. He has no idea why those particular colors attract smallmouth so well, but they do.

“I have a theory, and it’s worked all over the country, that when bass swim up and nip the jig but then swim away, I have the right colors, but the wrong style of trailer,” Lowen says, “so I rotate through the three different trailer styles I use. If I don’t have any followers at all, I have the wrong color, so I go through the different colors but use the same style of trailer. I’ll mix colors, too, like using a green jig with a black-and-blue trailer, just because it sometimes works.

“I honestly don’t believe it has anything to do with water color or clarity. It’s all about the mood of the bass and how aggressive they are.”

The Elite Series pro emphasizes the only way to gain confidence swimming a jig is to just keep doing it, because it will start attracting bass. During the 2006 Bassmaster Elite season, his rookie year as a pro, Lowen made the pay cut in his first five events just by swimming a jig, and this was on lakes he’d never seen before, including Amistad, Santee Cooper, Clarks Hill and even Grand Lake.

“During the Sam Rayburn Elite that year, my second tournament, I eventually finished fourth, but I lost a bass on a swimming jig that might have won the event for me,” he says. “My observer partner that day was Bob Sealy, who conducts the famous big bass tournaments across the South, and he said it was a legitimate 12- to 15-pounder. So, you know this is a technique that does attract big fish. Incidentally, losing that fish is what started me using the braided line I fish with today.”

Overall, Lowen’s theories and his expertise with this little-used presentation seem simple to follow, and with stories like that monster at Rayburn, it seems like swimming a jig would be part of every bass fisherman’s arsenal. He thinks one reason more bass fishermen don’t try swimming a jig, or at least don’t stay with it very long, is simply a lack of confidence and understanding of the presentation, but that’s true with every lure and technique.

Then again, Lowen himself thinks back to that fateful day on Tanners Creek so many years ago. He stumbled onto the swimming jig technique by accident himself, and today, two decades later, he considers it one of the best days of his life.