In the spring of 1967, when Ray Scott began promoting his All-American Bass Tournament at Beaver Lake, Arkansas, almost nobody believed in him or bought into his idea.

The Chamber of Commerce in Springdale, Ark., gave him office space but little else. His boss at the insurance company, for which Scott worked, said he’d hold his job open for a time, just in case. Even outdoor writers in the area were underwhelmed.

Bob Cobb was a striking exception. The first time he heard about Scott’s ideas for elevating tournament bass fishing into a true professional sport, the Tulsa Tribune outdoor writer was captivated.

Recently, I was reunited with Cobb, whom I worked for and learned from for the better part of two decades. Steve Bowman of JM Outdoors, B.A.S.S. Senior Editor Thomas Allen and I spent a fantastic afternoon with Cobb and Scott in Pintlala, Ala., interviewing the two for a “living history” documentary about the early days of bass fishing. (See Cobb’s article about that first bass tournament — held 50 years ago this month.)

“Why did you buy into Ray’s idea? What did you see that the others didn’t?” I asked him.

“He was as enthusiastic about bass fishing as I was,” Cobb said. “He had personality and charm and the lingo. So I went along. I liked Ray. I liked what he was doing, and I wanted to be a part of it.”

Through his connections with the fishing community in Tulsa, Cobb drummed up entries in the All-American, contributing mightily to the event’s success.

After Scott formed the Bass Anglers Sportsman Society (B.A.S.S.) and created Bassmaster Magazine in early 1968, he quickly realized he needed a professional to edit the magazine.

“Ray said he needed me because I could read and write, and those were shortcomings for him,” Cobb said.

Cobb was torn between staying in Tulsa and jumping on a bandwagon with a loose wheel or two. With a young family to provide for, he worried about the future of B.A.S.S.

“I was caught between a rock and a hard place,” Cobb said. In the end, Barbara Cobb’s mother, Mae Foster, convinced her daughter to support the move, saying, “If that’s what he wants to do it would be best if you’d go do it and make it happen.”

“If she hadn’t made those statements, I’d probably never have gone,” Cobb said.

The Cobbs began having second thoughts immediately upon moving to Alabama.

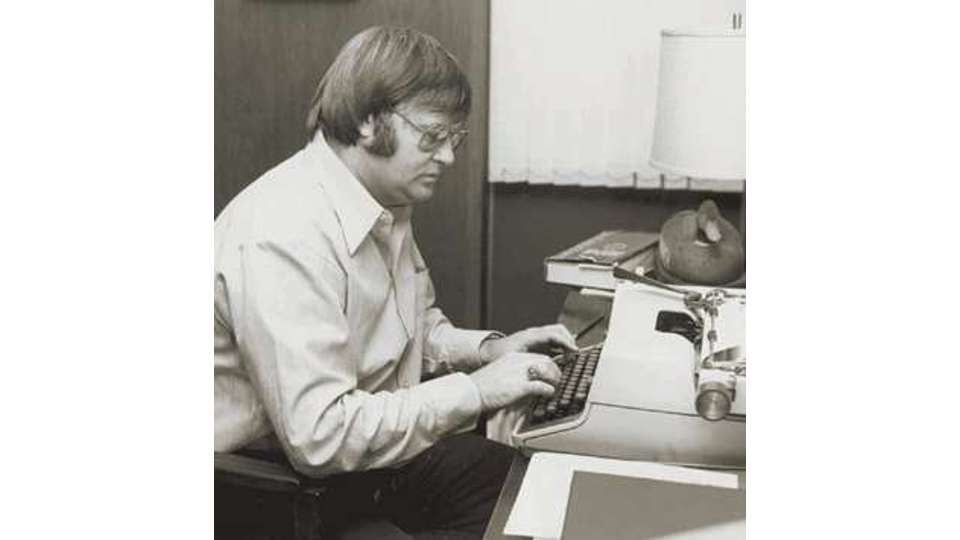

Scott turned over the files for Bassmaster and told Cobb to have at it. His office consisted of an architect’s drafting table, an old manual typewriter and a “pro throne” Scott had taken off the bow of a bass boat. The entire magazine files were stuffed in a cardboard box from a Montgomery-based company, Whitfield Pickles. Cobb still remembers the slogan on the side of the box: “The pickle with the perfect pucker, picked at the peak of perfection by particular pickle-picking people.”

When the Cobbs joined Ray Scott and his wife for dinner that night, Eunice Scott confided in Barbara, “Everybody at the church is praying for Ray, praying he’ll come to his senses and get a real job and take care of us.”

“Boy, I felt like the rug had come out from under me,” said Cobb. “I really didn’t know what the future was. But I had faith in Ray. And I had faith in the idea. We didn’t look back.”

I, for one, am grateful Cobb and his family made that leap of faith almost 50 years ago. Not only would B.A.S.S. have been a very different organization — if, indeed, it survived — but the sport of bass fishing itself would have been deprived of one of its greatest advocates.

With his homespun style and love for the lingo of bass fishing, Cobb turned the contents of that pickle box into what Time Magazine one day would call “The Bible of Bass Fishing.”

Scott and Cobb hatched the idea for the Bassmaster Classic early on, and with his gift for public relations, Cobb convinced the influencers among outdoor writers of the day to buy into bass fishing, to give it legitimacy.

There’s no denying that Scott is the father of modern bass fishing. But it’s also likely that, without Cobb alongside him, Scott’s dream would never have become reality.